This sums up pretty much everything I feel about what theatre should, or rather shouldn’t be doing. Whenever I read it or share it with other writers I get rousing cheers. This is important stuff here folks.

Guardian Unlimited: Arts blog – theatre

A message to young playwrights: don’t be so boring

Anthony Neilson

March 21, 2007 9:17 AM

http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/theatre/2007/03/dont_be_so_boring.html

I was part of a theatrical movement once. As with most movements, no one who

was a part of it noticed anything moving at the time. I still wouldn’t know if a journalist hadn’t told me. “In-Yer-Face”, it was called, which offended the more famous of my fellow movementarians, but I was just glad someone had noticed I was alive. As far as I can tell, In-Yer-Face was all about being horrid and writing about shit and buggery. I thought I was writing love stories.

Fifteen years on, there doesn’t seem to have been another movement, so I thought I’d try to start one. Unfortunately, despite being pretty sure the next movement will be absurdist in nature, I couldn’t think of a snappy name for it so I gave up on that. Then I thought I’d write a provocative Dogme-style manifesto, but I only came up with four rules, and I’ve already broken two of them in my new show. Then I thought I’d write Ten Commandments for young writers but a) that’s a little pompous, and b) there’s only one commandment worth a damn, and it’s this: THOU SHALT NOT BORE.

Boring an audience is the one true sin in theatre. We’ve been boring audiences for decades now, and they’ve responded by slowly withdrawing their patronage. I don’t care that the recent production of The Seagull at the Royal Court was sold out. To 95% of the population, the theatre (musicals aside for now) is an irrelevance. Of that 95%, we have managed to lure in maybe 10% at some point in their lives, and we’ve so swiftly and thoroughly bored them that they’ve never returned. They’re not the ones who broke the contract. They paid their money and expected entertainment; we sent them back into the night feeling bored, bullied and baffled. So what are we doing wrong?

The most depressing response I encounter when I’m chatting someone up and I ask them if they ever go to the theatre is this: “I should go but I don’t.” That emphatic “should” tells you all you need to know. Imagine it in other contexts: “I should play Grand Theft Auto”; “I should watch Strictly Come Dancing.” That “should” tells you that people see theatre-going not as entertainment but as self-improvement, and the critical/ academic establishment have to take some blame for that.

Many critics still believe theatre has a quasi-educational/political role; that a play posits an argument that the playwright then proves or disproves. It is in a critic’s interest to propagate this idea because it makes criticism easier; one can agree or disagree with what they perceive to be the author’s conclusion. It is not that a play cannot be quasi-educational, or even overtly political – just that debate should organically arise out of narrative.

But this reductive notion persists and has infected playwriting root and branch.

I can’t tell you how often I’ve asked an aspiring writer what they’re working on, and they reply with something like: “I’m writing a play about racism.” On further investigation, you find that this play has no story and they’ve been stuck on page 10 for the past year; yet they’re still hell-bent on writing it. You can be fairly sure the play, should it ever be finished, will conclude that racism is a bad thing. The writer is not interested in exploring the traces of racism that may lie dormant within their psyche, nor in making the case for selective racism (just to be “provocative”).

This is the writer using the play to project their preferred image of themselves; the ego intruding on art; the kind of literary posing that is fed by the idea of debate-led theatre. And if you think that example sounds naive, substitute the word “racism” with “George Bush” or “Iraq” or “New Labour”. Sound familiar?

Newspapers, or news programmes, are the places for debates, not the theatre.

The general public don’t think: “Should I go to the theatre Friday, or that socio-political theory class?” Further education is not the competition. The pub is the competition, the cinema, a night in with a curry and a DVD. We are entertainers. What we do is not as important to society as brain surgery, or even refuse collection. But when the brain surgeon and the refuse collector finish work, they come to us and it is our job to entertain them – not necessarily just to distract them, but to stimulate, to refresh, to engage them.

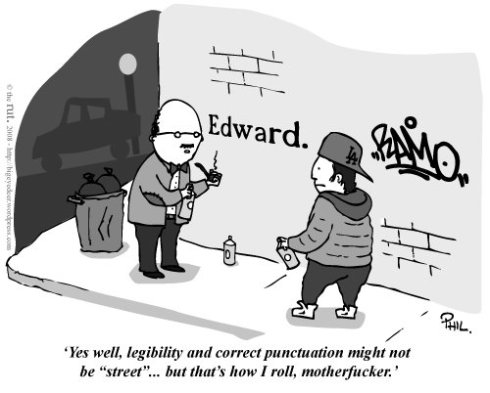

That’s our place in the scheme of things, and it’s a responsibility we should take seriously. To let our egos intrude is like the brain surgeon writing “Jake Was Here” on your frontal lobe before he puts your scalp back. The way to circumvent ego (and thus reduces the risk of boring) is to make story our god. Find a story that interests you and tell it. Don’t ask yourself why a story interests you; we can no more choose this than who we fall in love with. You may not be what you think you are – not as kind, as liberal, as original as you ought to be – and yes, the story (if you are true to it) will find that out. But while your attention is taken up with its mechanics, some truth may seep out, and that is the lifeblood of good, exciting art.

I’m not saying we should all be Terence Rattigan. The story you tell can be about anything, told in whatever form is most effective. But that brings me to my next point: accessibility.

To this day, I still leave plays wondering what on earth they were about. I used to feel stupid for not “getting it”, but not any more, because this I know: it’s the artist’s failure, not mine. It’s not necessary that every audience member gets every level on which a play works (several, if it’s good), but it’s important that they’ve understood it, from moment to moment, while watching it. Little Red Riding Hood is completely understandable to five-year olds and yet academics are still writing papers on its deeper meanings. This profound simplicity is what all playwrights should aspire to. Not only does it render a play accessible (on at least a narrative level) to an inexperienced theatregoer, it also encourages the widest possible scope for interpretation. Much as it depresses me, as a living writer, that the theatre business is still so in thrall to dead playwrights, this narrative clarity is key to the classics’ longevity.

So tell your story as you wish – but for God’s sake, if it plays best as a linear narrative, don’t tart it up for the sake of feeling innovative. There’s no shame in a good story, well told. Contrary to the popular maxim, do think about your audience. Ask yourself if your non-theatre-going friends or relatives would at least get the gist of it. If they wouldn’t, your work is not yet done. (That said, never compromise on the grounds of what they may be offended by. Truth is not always comfortable but a dishonest play is usually dull.)

Two asides. One, dialogue: there’s a lot of poetic dialogue around.

Sometimes a play is narratively accessible but the dialogue is mannered to the point of incomprehensibility. Some people like it, but I’m suspicious. Poetic dialogue, done badly, leaves no room for subtext. A lack of subtext is fundamentally undramatic. And boring.

And two, duration: many plays are far too long. All writers should be made to visit the venue where their play is to be performed and sit in the seats with a stopwatch. When your arse and spine start to sing, check the watch. That’s your running time. Exceed it at your peril.

Now – musicals. Much as the synopsis of We Will Rock You sounds abysmal, it’s pulling in more punters a night than some “serious” shows attract in a week. There’s a dangerously dismissive response to this uncomfortable truth among many of my fellow practitioners, but it’s not hard to figure out why this might be. Musical theatre offers song and dance, of course; a certain unpretentiousness; a tangible sense of “liveness”; magic; and, most importantly, spectacle.

It is time the “serious” theatre learns this lesson. We have to give the audiences what they can’t get anywhere else. Debate they can get in a newspaper. Reality – well, they can get that on TV. We can offer them “liveness”, but few plays, or productions, take advantage of this. Too many screenplays masquerading as plays and an over-reliance on mixed media have imbued the theatre with a heaviness it’s not best suited to. Some may argue that technology is the key to spectacle, but most theatres can’t compete with the West End technologically. The spectacle we can offer is the spectacle of imagination in flight. I’ve heard audiences gasp at turns of plot, at a location conjured by actors, at the shock of a truth being spoken, at the audacity of a moment. There is nothing more magical and nothing – nothing – less boring.

Oh, and if you can get a song or two in there, all the better. My show has three.

Tags: advice, Anthony Nielsen, boring, theatre